Theme Landscape

Theme Landscape is a brief description of how Ragunda's landscape has been formed and developed from 2,000 million years back to the present day.

The formation of the old bedrock

Some 2,000 million years ago a sea covered most of what we now call Northern Sweden. For many hundred millions of years, large quantities of sediment were deposited on the bottom of the sea. The material was abraded into gravel, sand and mud which were carried by rivers and the wind into the sea.

On the bottom of the sea thick layers of sediment were formed. As the layers of sediment grew thicker, they were compressed through their sheer weight, and eventually the sediments transformed into rock.

The remains of the old sea and its sediment have formed the bedrock nowadays covering most of mid-Sweden.

Melted masses of rock formed magma chambers

1,500 million years ago a weak zone appeared, reaching from the present southern Finland in the east, westwards through Ragunda and onwards towards the mountain range of today. In this region, the outmost layer of the earth, the crust was stretched and thinning. The pressure on the underlying rock and melted rock mass, magma, was reduced. The reduced pressure enabled two kinds of magmas, formed deep within the earth, to push upwards through the older bedrock aiming for the earth´s surface, rather like bubbles when you open a bottle of sparkling water.

When the magmas failed to rise any higher towards the surface they remained at a depth of about three kilometres. There they formed several magma chambers, a bit like enormous balloons. The magma chambers raised the crust of the earth to form rounded shapes. When in due course the magmas cooled and became solid they formed rocks. One of the magmas was dark, almost black and became gabbro, while the other one was red and became granite.

Younger rocks pushed upwards in cracks and rifts

The youngest rocks in Ragunda pushed upwards in cracks and rifts in the mountain. It was long after the magma chambers had formed, at a stage when the mountain had had time to cool and crack. It is not clear when this happened. To determine the age of the porphyry, more detailed investigations need to be carried out.

One of the younger types of rock in this area is porphyry. Magma of porphyry has pushed upwards through the cracks in the mountain and formed galleries. They can be seen at Stadsberget.

The wind, water and ice eroded the rock surface

Following these processes came a period of several hundred million years without any significant changes in the area. During the period the rock was abraded, i. e. worn down by erosion. The loose material was carried off by the wind, water and ice and eventually a more or less flat rock surface had been formed, a peneplain.

Crevices crumbled away and became deep valleys

Some 200-100 million years ago, Sweden was part of the supercontinent Pangea. Our country was positioned in more southerly latitude and was covered by desert. The dry and warm climate enabled crevices to crumble away, affecting the flat rock surface.

The crumbling hollowed out the cracks and crevices and through erosion the material was carried off. The most easily carved out parts of the peneplain became valleys while the more resilient parts were preserved as hills.

In our days, the peneplain constitutes the tops of the hills. You can see it from Kullstabergets utsiktsplats and Böle-Hoo utsiktsplats.

Melting water carried away lighter material

The landscape we look at nowadays was mainly formed by and in the ice ages over the past 2.6 million years, and especially during the most recent called the Weichselian, and the second most recent, Saalian, that have impacted the landscape.

20,000 years ago, during the Weichselian, a sheet of ice several kilometres thick – the inland ice - covered all of Sweden. From then on the ice started to melt and diminish in size. To start with, the melting was slow but gradually the process quickened. Geologists are not entirely certain but Ragunda was probably free from ice some 10,000 years ago.

At the time when the ice was melting the most, enormous quantities of water rushed through the landscape. The melting water carried away lighter material such as sand and gravel and wore down the rocks. What remained was clean-washed, rounded large slabs and boulders that the water was unable to carry off.

At Nornan you can see giant boulders left by the masses of water and at Getgrottan you can see other boulders probably carried there by ice during one of the ice ages.

Melting water formed new land areas

Once the surge of water slowed down and no longer was capable of carrying that much material, the sand and gravel sank to the bottom. For a period the ice made a longer break here in its melting. Then a lot of melting water with material flowed out in one and the same place. In this way, larger, new land areas could be formed. Some examples of land areas built up by material from the melting ice are the ridge Getryggen and the plateau of sandy ice river material at Döviken – Zorbcenter.

Blocks of ice formed kettle holes and kettle lakes

In the area around Getryggen there are kettle holes and kettle lakes. Kettle lakes are water-filled kettle holes; they were formed when ice blocks came loose and were embedded in the material that the melting ice had left behind. The material solidified around the blocks of ice and when the ice blocks melted, holes - kettles - were formed of the same size as the ice blocks had been.

If you want to study another kettle hole you can visit Fors skogskyrkogård.

The land uplift uncovers land areas

As the most recent inland ice disappeared from Ragunda the melting water carried along large quantities of fine material. The material was deposited in the valley of the River Indalsälven, at that time a bay in the Baltic Sea.

Ever since the ice melted there is an ongoing uplift of land in this country. The heavy ice pressed down the earth’s crust as much as 1,000 metres. As the climate grew milder and the ice melted the pressure on the crust was lessened and the land started rising anew. In our days the land uplift is almost one centimetre per year.

Because of the land uplift it is nowadays possible to find the material deposited in the valleys as well as far up on the hills, like at Ammerån Våle.

Flowing water continues to alter the landscape

Ever since the ice melted the flowing water has continued to alter the landscape in the process of bringing, wearing down and transporting materials such as sand, gravel and mud. New land has been formed and continues to be formed with the material deposited. An example of this are the sandbanks found in the River Ammerån On some of them roots and growth will bind the sediment they are formed by, making it difficult for the water to carry off the material, even at the strongest spring flood.

Whirling water with sand, gravel and stones formed giant caves

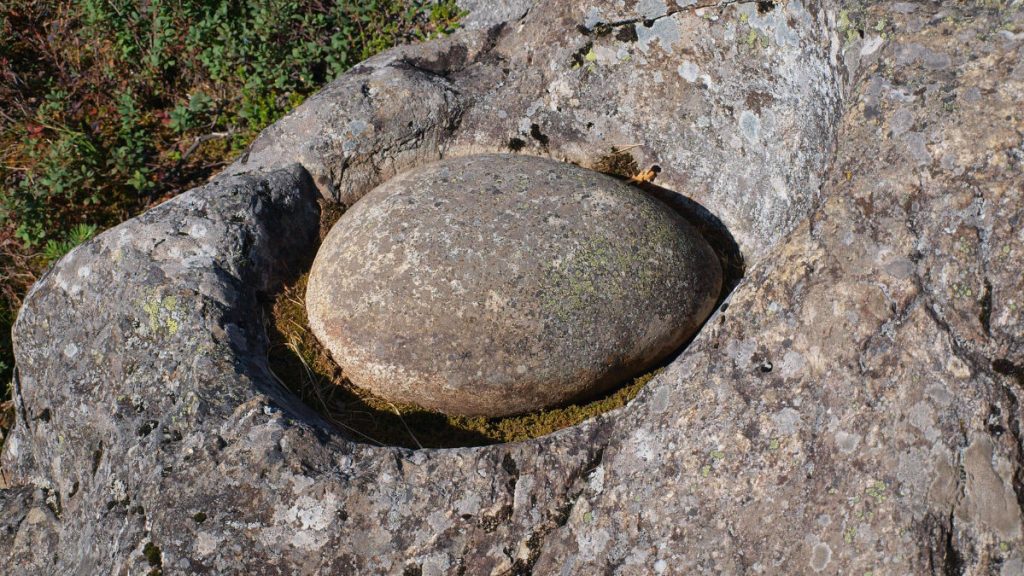

In the dry riverbed in Döda fallet are giant holes in the bedrock, some of them quite deep and others shallow. The giant caves were formed when water flowing for thousands of years undermined the bedrock. Small stones, gravel and sand whirled with the water for a long time and carved out the holes in the rock. At the same time the surface of the giant cave was polished smooth. In some of the caves lies a smooth, oval stone, called a runner stone. In older days, folklore told that giants used the cavities for cooking. That is why they are called giant kettles.

Natural disaster caused by man

The emptying of Lake Ragundasjön is one of the worst natural disasters in Swedish history caused by a man. On 6 June 1796 Magnus Huss, “Vildhussen”, was attempting to redirect the water past the 30-metre high waterfall Storforsen. Things did not go according to his plans and Lake Ragundasjön upstream from the waterfall was emptied in only a few hours. What remained was a dead waterfall, Döda fallet, together with the nearly 800 metres long riverbed, a canyon.