Döda fallet

Visible effects of the abrasive force of water

On 6 June 1796 Magnus Huss was attempting to redirect the water past the 30-metre high waterfall Storforsen. Things did not go according to his plans and Lake Ragundasjön upstream from the waterfall was emptied in only a few hours. What remained was a dead waterfall, Döda fallet, together with the 800 metres long dry riverbed, a canyon. Döda fallet is the centre of the geopark. Here is a restaurant, a visitors´ centre, wide wooden ramps, hard-packed gravel ground, a nature path and picnic facilities.

Remmen

Storforsen had long been a problem. For the forest owners who lived upstream of the waterfall, it was not possible to float timber down to the sawmills on the coast. The wood was broken in the 30 metre high fall. Another problem was that the salmon in the river could not climb the fall. So it was only downstream that it was possible to catch the fish. There was also a dream of creating a water trail from the Baltic Sea to Lake Storsjön.

Magnus Huss – also called Vildhussen – was hired to solve the problems by digging a canal past Storforsen. He began digging the canal in a ridge called Remmen (see map). The ridge was 65 metres high and 300 metres wide and lay across the present valley of Indalsälven. Upstream, the ridge bordered to the shore of Lake Ragundasjön in Sandviken.

However Vildhussen was unaware that the ridge was not only formed by sand and gravel. Here was also silt, a type of soil with the capacity to be saturated by water. When the silt is incapable of absorbing more water it loses all of its stability, it may even become liquid. What Huss also didn't know was that Remmen rested on a deep ravine, an older riverbed.

During the night of 6 June 1796 the ridge burst and all of Lake Ragundasjön was emptied in only a few hours. Storforsen became Döda fallet (the dead fall) and the River Indalsälven found a new waterway. The ridge was washed away and a brand new landscape formed.

Lokängarna

Where the River Indalsälven runs nowadays lay previously the fertile meadows Lokängarna, where the farmers in Västerede grew hay.

When the river burst through to the new waterway the hayfields were washed away, together with 16 barns. The same thing happened further downstream: barns, jetties, saw-mills, mills and fishing sites were carried away by the strong current. The damages were unfathomable. After the disaster, the soil became dry and nutrient poor. Nowadays, mostly pine trees grow here.

The dry riverbed

The most obvious feature in the Döda fallet area is the riverbed. There ran the white waters of Storforsen until Lake Ragundasjön vanished. At that time here had been the outlet of the lake for some 7,000 years. Since most of the area is dried out you can study the effects of the force of the rushing water, the most destructive process there is. Here you will find large boulders, plunge basins and giant kettles. In the riverbed enormous masses of the melting water from the inland ice have also rushed forth and worn down the bedrock.

Large boulders

In the riverbed are the large boulders that the water was incapable of carrying away. Not even the strong currents of the Storforsen fall could cope with these.

In 2020, scientists discovered a previously unknown process that could explain the formation of such a large block field as you can see here. If you are interested, you can read more here (in Swedish): Nyupptäckt process bakom istida landskapsformer.

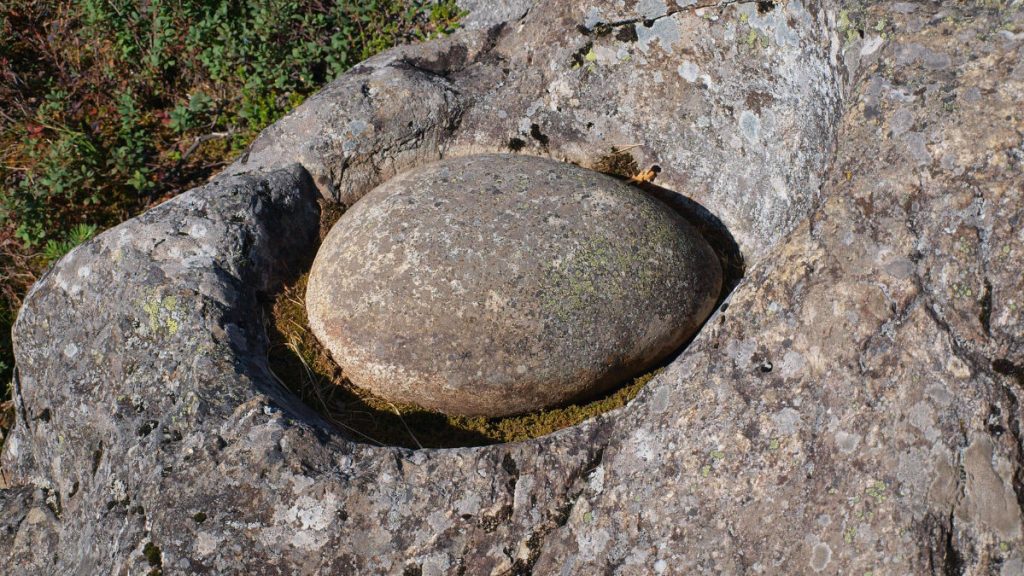

Giant kettles

In the dry river bed in Döda fallet there are several pits in the bedrock. Some are small and some are large. Some are deep and some shallow. The pits are called giant kettles. They were formed when water flowing for thousands of years undermined the bedrock. Small stones, gravel and sand whirled with the water for a long time and carved out the holes in the rock. In some of the caves lies a smooth, oval stone, called a runner stone. In older days, folklore told that giants used the cavities for cooking. That is why they are called giant kettles.

Plunge basins

Below what used to be the Storforsen waterfall you will see some large round pools or basins. These are the plunge basins where the water coming down the fall landed with full force and dug into the bedrock. In the process as the rock wall in the waterfall was abraded, the fall moved slowly upstream, thereby creating new plunge basins. This is why you can see several plunge basins at different distances from the edge of the waterfall.

Lintjärn

It was in Lintjärn that the canyon began to form approximately 7 000 years ago. It was here that the rapid was born, which would later become Storforsen 800 m upstream. The rapid slowly worked its way backwards through the bedrock. The currents wore down the bedrock to create the steep vertical walls in the channel. The bedrock here is heavily cracked, which helps the water to create whirls that serve to wear down the rock with the help of gravel and sand. In the winter, at low water the liquid gathered in the cracks would freeze and blast loose more rock. All of the above have served to design the canyon.

The canyon

Lake Ragundasjön was formed 7,600 years ago when the land uplift gradually raised the rock threshold at Döda fallet to such an extent that the lake was cut off from the Ragunda fiord, at the time a part of the Baltic Sea. The lake’s outlet ran at that rock threshold and here formed a waterfall which grew higher as the land uplift continued. The water’s capacity to break down the bedrock is due to various reasons. The factors that affect the erosion include the quantity of sand, gravel and stones that is carried along by the water, the angle of the drop, and the hardness of the bedrock. In Sweden canyons are rare, since our bedrock is mostly quite hard and difficult to wear down.

Herkulesgruvan

The mine Herkulesgruvan is a ten metre deep mining pit. The exploiters were hoping for silver but instead found graphite. The mine dates back to the mid-1800s but failed to make a success and was soon closed down. There was not enough mineral to justify a continuation of the mining. The rust-brown streaks in the rock are iron deposits.

The rock at the mine has started to abrade and there have been several caving-ins and the mine is thus for safety reasons closed to visitors.

More information

The nature reserve Döda fallet

More site photos

Places to visit nearby

Practicalities

Accessibility

See Accessibility.

Activities

You can walk on the wooden ramps in the fall area or on a nature path stretching for 3.5 kilometres nature trail around Döda fallet. The path is cleared and in parts duck-boarded. At steep sections there are ropes and wooden banisters to facilitate passage. See also Activities in Ragunda.

Eating and drinking

The restaurant in Döda fallet is open during the summer. See also Eating and drinking in Ragunda.

Accommodation

Missing on site, but various options are available nearby. See Accommodation in Ragunda.

Getting here

SWEREF 99 TM N: 6 992618 E: 576853

WGS84 N: 63,05493° E: 16,52022°